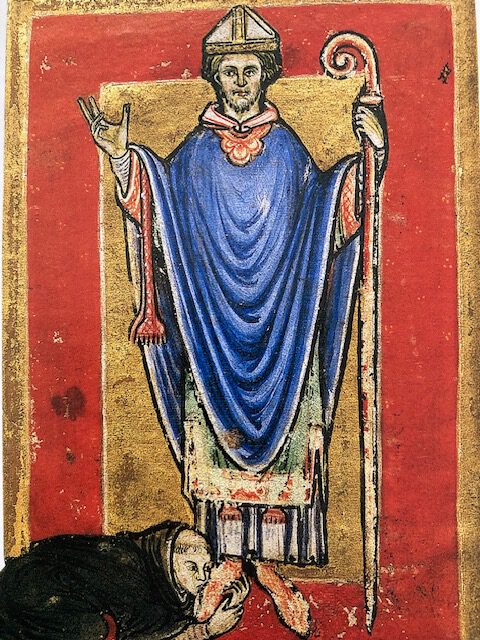

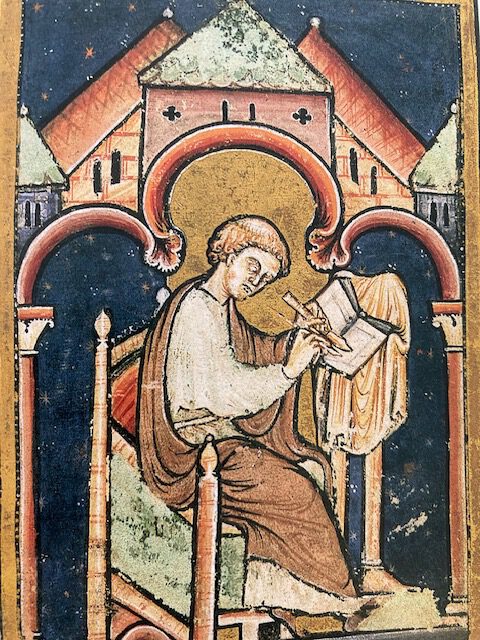

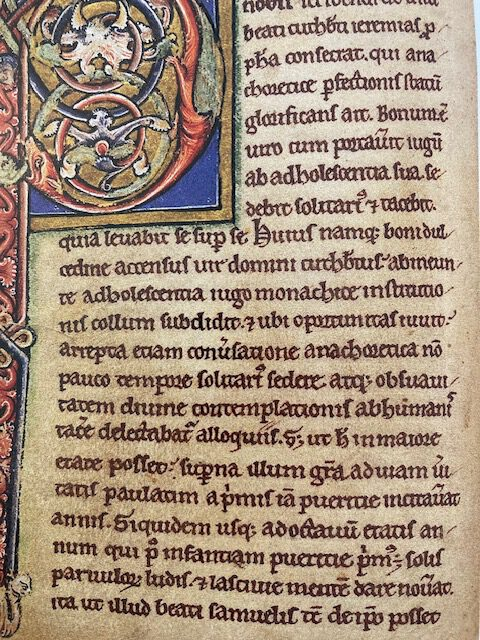

Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: Chapter III

We are starting our exploration of Cuthbert’s life with chapter 3 which is the first event depicted in the images of the Yates Thompson collection. Cuthbert’s earlier life is described in some detail by Bede, but has not been illustrated by the scribes. There are stories of an ebullient youthful Cuthbert “because he was agile by nature and quick-witted, he very often used to prevail over his rivals in play, so that sometimes, when the rest were tired, he, being still untired, would triumphantly look round to see whether any of them were willing to contend with him again”. But around the age of eight, he was surprised to be addressed as “bishop” by a very young child, and this prophetic challenge seems to have shifted his direction into a more prayerful and thoughtful lifestyle. The events of Chapter 3 take place during this transitional period of his life. As a teenager he is already regarded to be a person of prayer. Bede writes:

HOW CUTHBERT CHANGED THE WINDS BY PRAYER, AND BROUGHT THE SCATTERED SHIPS SAFE TO LAND

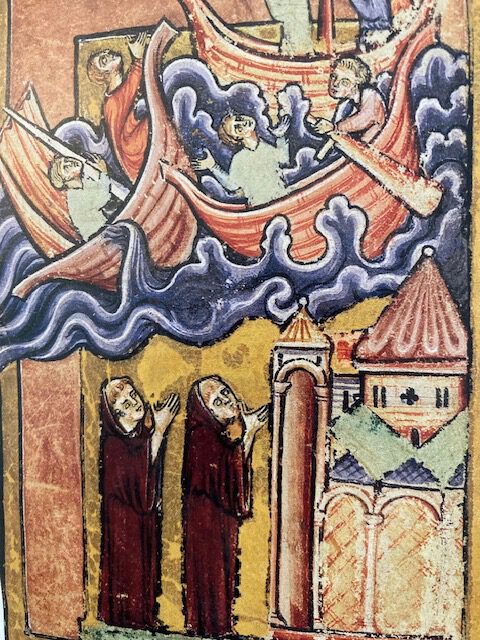

FROM this time the lad becoming devoted to the Lord, as he afterwards assured his friends, often prayed to God amid dangers that surrounded him, and was defended by angelic assistance; nay, even in behalf of others who were in any danger, his benevolent piety sent forth prayers to God, and he was heard by Him who listens to the cry of the poor, and the men were rescued out of all their tribulations. There is, moreover, a monastery lying towards the south, not far from the mouth of the river Tyne, at that time consisting of monks, but now changed, like all other human things, by time, and inhabited by a noble company of virgins, dedicated to Christ. Now, as these pious servants of God were gone to bring from a distance in ships, up the above-named river, some timber for the use of the monastery, and had already come opposite the place where they were to bring the ships to land, behold a violent wind, rising from the west, carried away their ships, and scattered them to a distance from the river’s mouth.

Two monks praying at the monastery of Tynemouth interceding with God on behalf of those whom they perceived to be even now in imminent risk of death..

The brethren, seeing this from the monastery, launched some boats into the river, and tried to succour those who were on board the vessels, but were unable, because the force of the tide and violence of the winds overcame them. In despair therefore of human aid, they had recourse to God, and issuing forth from the monastery, they gathered themselves together on a point of rock, near which the vessels were tossing in the sea: here they bent their knees, and supplicated the Lord for those whom they saw under such imminent danger of destruction. But the Divine will was in no haste to grant these vows, however earnest; and this was, without a doubt, in order that it might be seen what effect was in Cuthbert’s prayers. For there was a large multitude of people standing on the other bank of the river and Cuthbert also was among them. Whilst the monks were looking on in sorrow, seeing the vessels, five in number, hurried rapidly out to sea, so that they looked like five sea-birds on the waves, the multitude began to deride their manner of life, as if they had deserved to suffer this loss, by abandoning the usual modes of life, and framing for themselves new rules by which to guide their conduct.

Cuthbert restrained the insults of the blasphemers, saying, “What are you doing, my brethren, in thus reviling those whom you see hurried to destruction ? Would it not be better and more humane to entreat the Lord in their behalf, than thus to take delight in their misfortunes? ” But the rustics, turning on him with angry minds and angry mouths, exclaimed, ” Nobody shall pray for them: may God spare none of them ! for they have taken away from men the ancient rites and customs, and how the new ones are to be attended to, nobody knows. ” At this reply, Cuthbert fell on his knees to pray, and bent his head towards the earth; immediately the power of the winds was checked, the vessels, with their conductors rejoicing, were cast upon the land near the monastery, at the place intended. The rustics blushing for their infidelity, both on the spot extolled the faith of Cuthbert as it deserved, and never afterwards ceased to extol it: so that one of the most worthy brothers of our monastery, from whose mouth I received this narrative, said that he had often, in company with many others, heard it related by one of those who were present, a man of the most rustic simplicity, and altogether incapable of telling an untruth.

Cuthbert praying on the banks of the River Tyne:

***********************************************************************************************************

I am especially charmed by Bede’s passing comment on the “monastery lying towards the south, not far from the mouth of the river Tyne, at that time consisting of monks, but now changed, like all other human things, by time, and inhabited by a noble company of virgins, dedicated to Christ.” The women have taken over the monastery! – I can sense his rueful resignation. 😉

But what is the point of this story? prayer?

Canon 603 is adamant that the prayer of the hermit be “assiduous”: [hermits] withdraw further from the world and devote their lives to the praise of God and the salvation of the world through … assiduous prayer”. What does this mean in practice?

Bede uses the references of his story about St Cuthbert to emphasise the particular power of Cuthbert’s prayer. He presents it as a capacity to engage with the elements – the wind, the rain, the stormy sea – in the same way as Jesus did on the Lake of Galilee. We are to understand Cuthbert as a conduit of the charisms of the Christ figure who can control all of creation and thus rescue men “out of all their tribulations” through his prayer.

The prayers of the other monks – well-intentioned and “earnest” as they are – “they bent their knees, and supplicated the Lord for those whom they saw under such imminent danger of destruction” appear to fail in their intercession. Then Cuthbert kneels down and prays, “bending his head to the ground , and immediately the violent wind turned about and bore the rafts safe and sound to land, amid the rejoicings of those who were guiding them.” How are we to discern this difference in apparent outcome? What was it that made Cuthbert’s prayer effective, and those of the monks not-so-much? Even Bede seems confused – he offers the solution that the “Divine will” waited for Cuthbert’s prayer in order to advertise Cuthbert’s holiness and his favour with God; to promote him as a guide and teacher.

But this is such a usual happening – the prayers of the masses – for peace, for health, for security, are seldom answered in the way that Cuthbert seems able to invoke. We don’t seem to have the capacity to invoke the wind and the rain and to change the weather forecast at our convenience! How are we to resolve this discrepancy? How are we challenged, or discouraged, or defeated by this repeated experience? How do we deal with the realistic expectation that we may not be miracle-workers?

At the beginning of my hermitage, when I was a bit overwhelmed by it all, I asked my spiritual director what was expected of me when the “please pray for …” requests started coming in. From the experience of many years in religious life, his response was: “God hears the prayer already, as it is asked for. The work of the prayer is done – in the asking – by the person who is doing the asking. That is the prayer. They have turned to God, The words have been spoken. God has heard.

Your job then is to hold the silence that follows”

So how to “hold the silence?

One of the things that I have begun to learn over 23 years of hermitting has been “prayerful-living”. I think it might have echoes in the methods of mindfulness which are so popular nowadays as a respite from the media fuzz. My tendency to need to get-things-done can lead to a stressful chaos of half-finished tasks, my mind always on the next one. My version of prayerful-living uses a simple silent mantra: this is what we are doing to keep me centred in the moment; to keep me fully involved in whatever task – prayer, housework, gardening, DIY – I might be engaged in. this is what we are doing. This is a silent event; it is a gasp of acknowledgement. No matter how busy or active I might be in my work, I try to embrace the stillness of each moment. This is what we are doing

Hermitage is fundamentally a life of prayer. And I do indeed spend some time each day in focussed silence and stillness and listening. Sitting intentionally in God’s presence. These are the essential, but generally least remarkable times of my day! The directness of God’s gaze can be uncomfortable, challenging, or occasionally reassuring. And staying in that place when there is stuff to face, or other pressing matters to be getting on with, can be difficult: this is what we are doing. We stay a little longer.

But most of my silence-with-God goes on with God as a companion at my side, opposite me at the work table, enjoying the sunshine with me; the cosiness of a warm autumnal evening, walking through the woodlands near my bungalow, the juxtaposition of a book and a mug on a table. This is what we are doing. That refuge of the moment might be a place of safety where I receive bad news, or it might be a place of sadness, or anxiety, or tiredness, or pain: “this” – this distress and discomfort and sorrow – this unbearable thing: this is what we are doing.

Who is “we”?

This is what we are doing. The “we” refers to God-and-me (or you!): the silence-of-us. But within that silent space are all the prayers we are holding; each and every person and the prayers already offered, and their unspoken prayers known only to God. They are fully present in that “we”, in each silent moment of hermitage.

Perhaps we can trust that the prayers of the Tynemouth monks were heard by God. Perhaps we can trust that those prayers opened a space in the crowd for Cuthbert to step forward and bend down and put his face to the ground to hold silence with God. Perhaps the wind and the rain put their faces to the ground and were silent with him.

Perhaps the silent space created by our prayers gives others a place where miracles can happen?

[hermits] withdraw further from the world and devote their lives to the praise of God and the salvation of the world through … assiduous prayer”. Canon 603

This text is part of the Internet Medieval Source Book. The Sourcebook is a collection of public domain and copy-permitted texts related to medieval and Byzantine history. Unless otherwise indicated the specific electronic form of the document is copyright. Permission is granted for electronic copying, distribution in print form for educational purposes and personal use. If you do reduplicate the document, indicate the source. No permission is granted for commercial use. © Paul Halsall June 1997 halsall@murray.fordham.edu