Attentiveness: Bede Life of Cuthbert: Chapter X

This story of Cuthbert praying through the night, standing in the North Sea, and being warmed and comforted afterwards by the sea-otters is one of the most feted stories of Cuthbert. It is often presented as a story of his legendary capacity for assiduous penance! Which might well be the case. But I like to interpret it differently:

I would suggest that it is night time. Cuthbert has spent a long and arduous day doing his work in the monastery. So much of his prayer time must take place at night. If you have ever tried to keep vigil in a church overnight, then you will know quite how difficult it is to remain awake and alert. I believe that Cuthbert stood in the sea simply in order to stay awake!

HOW CUTHBERT PASSED THE NIGHT IN THE SEA, PRAYING; AND WHEN HE WAS COME OUT, TWO ANIMALS OF THE SEA DID HIM REVERENCE; AND HOW THE BROTHER, WHO SAW THOSE THINGS, BEING IN FEAR, WAS ENCOURAGED BY CUTHBERT

WHEN this holy man was thus acquiring renown by his virtues and miracles, Ebbe, a pious woman and handmaid of Christ, was the head of a monastery at a place called the city of Coludi, remarkable both for piety and noble birth, for she was half-sister of King Oswy. She sent messengers to the man of God, entreating him to come and visit her monastery. This loving message from the handmaid of his Lord he could not treat with neglect, but, coming to the place and stopping several days there, he confirmed, by his life and conversation, the way of truth which he taught.

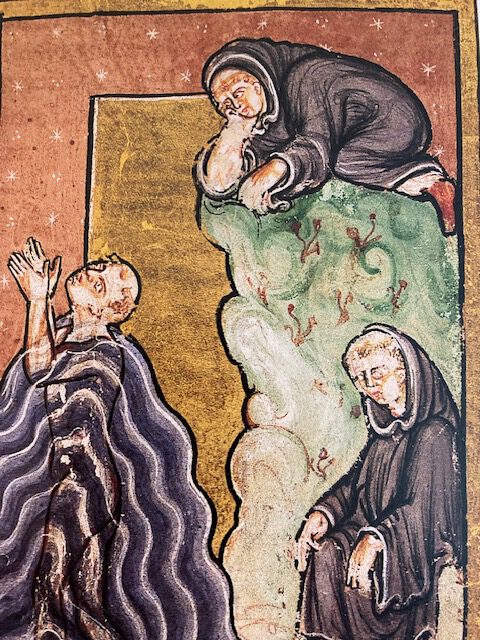

Here also, as elsewhere, he would go forth, when others were asleep, and having spent the night in watchfulness return home at the hour of morning-prayer. Now one night, a brother of the monastery, seeing him go out alone followed him privately to see what he should do. But he when he left the monastery, went down to the sea, which flows beneath, and going into it, until the water reached his neck and arms, spent the night in praising God. When the dawn of day approached, he came out of the water, and, falling on his knees, began to pray again. Whilst he was doing this, two quadrupeds, called otters, came up from the sea, and, lying down before him on the sand, breathed upon his feet, and wiped them with their hair after which, having received his blessing, they returned to their native element.

Cuthbert himself returned home in time to join in the accustomed hymns with the other brethren. The brother, who waited for him on the heights, was so terrified that he could hardly reach home; and early in the morning he came and fell at his feet, asking his pardon, for he did not doubt that Cuthbert was fully acquainted with all that had taken place.

To whom Cuthbert replied, ” What is the matter, my brother ? What have you done? Did you follow me to see what I was about to do? I forgive you for it on one condition,-that you tell it to nobody before my death.” In this he followed the example of our Lord, who, when He showed his glory to his disciples on the mountain, said, ” See that you tell no man, until the Son of man be risen from the dead.” When the brother had assented to this condition, he give him his blessing, and released him from all his trouble. The man concealed this miracle during St. Cuthbert’s life; but, after his death, took care to tell it to as many persons as he was able.

***********************************************************************************************************

I am moved by these three images of attentiveness: Cuthbert giving all his attention to God in his prayer, the chill waters of the North Sea keeping him awake; the otters eagerly attentive to Cuthbert’s needs – I like to think of them playing around him to comfort him even whilst he is standing in the water, and then, alert to his needs, drying and warming him up on the dry land. Finally the attentiveness of the spying monk. It is difficult to know why he was so alarmed at what he had seen. Perhaps it was the realisation that he had been an inappropriate witness to moments of great intimacy.

There is a further example of attentiveness when Cuthbert discerns the discomfort in the voyeur monk – and when the monk discovers this in himself.

C603 requires attentiveness in its living. The silence is not a passive silence but an attentive silence. We try to stay awake and alert to the voice of God. The guidance to C603 says “The expression solitudinis silentio (the solitude of silence) … emphasises that the hermit’s own silence is not reduced to the absence of voices or noises deriving from physical isolation, and can no longer be an imposed condition of the outside: it is the attitude fundamental which expresses a radical availability to listen to God. HLPC 14

This same “radical availability” to God is also required by the Desert dwellers. St Anthony of the Desert offered, “Whoever you may be, always have God before your eyes; whatever you do, do it according to the testimony of the holy Scriptures; in whatever place you live, do not easily leave it.” I find it interesting that this is so closely aligned to the mindfulness teaching of contemporary mental health training. His advice to Abba Pambo’s question of “What must I do?” is even more specific, “Do not trust in your own righteousness, do not worry about the past, but control your tongue and your stomach.”

I do not know if there is a link between the silence which Cuthbert requires of the watching monk, and that which Anthony requires of Abba Pambo. But the trope of “watch your tongue and your stomach” seems an eminently sensible and practicable way to begin to grow in attentiveness!