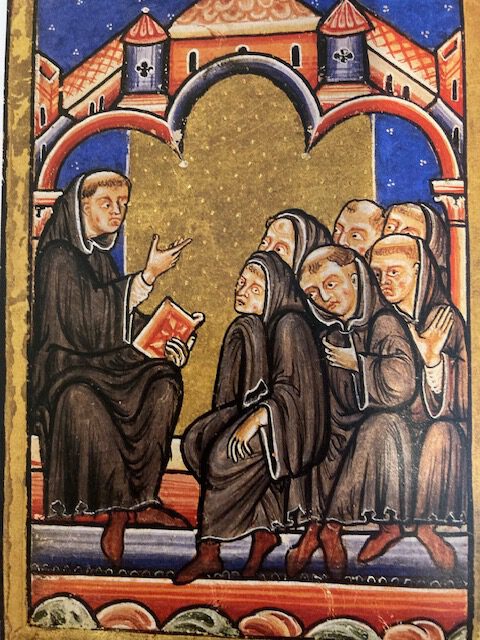

Perseverance: Bede’s Life of St Cuthbert: Chapter XVI

This is another of my favourite stories/images – it is so very human – Cuthbert faced with a community of disgruntled men, and learning how best to guide and encourage them. The faces on them all! You can almost hear Cuthbert counting to ten under his breath with exasperation, and the monks muttering stolidly in protest. And I enjoy the detail in this story of monastic life – the inheritance of previous generations of monks, the insistence on tradition, the petulance of the monks who clearly don’t like being disturbed in their sleep; Cuthbert’s methods of keeping awake, “making something with his hands, thus beguiling his sleepiness by labour; or, perhaps, he walked round the island, diligently examining every thing therein, and by this exercise relieved the tediousness of psalmody and watching.” and the acknowledgement that psalms can sometimes be tedious! And finally, the little hint that Cuthbert might not have been the most melodic of psalmsters … “it was the spirit which groaned within him rather than the note of singing“. It seems Bede was a perceptive – and trying-to-be-diplomatic – writer!

HOW HE LIVED AND TAUGHT IN THE MONASTERY OF LINDISFARNE

WHILST this venerable servant of the Lord was thus during many years, distinguishing himself by such signs of spiritual excellence in the monastery of Melrose, its reverend abbot, Eata, transferred him to the monastery in the island of Lindisfarne, that there also he might teach the rules of monastic perfection with the authority of its governor, and illustrate it by the example of his virtue; for the same reverend abbot had both monasteries under his jurisdiction. And no one should wonder that, though the island of Lindisfarne is small, we have above made mention of a bishop, and now of an abbot and monks; for the case is really so. For the same island, inhabited by servants of the Lord, contains both, and all are monks. For Aidan, who was the first bishop of that place, was a monk, and with all his followers lived according to the monastic rule. Wherefore all the principals of that place from him to the present time exercise the episcopal office; so that, whilst the monastery is governed by the abbot, whom they, with the consent of the brethren, have elected, all the priests, deacons, singers, readers, and other ecclesiastical officers of different ranks, observe the monastic rule in every respect, as well as the bishop himself.

The blessed pope Gregory showed that he approved this mode of life, when in answer to Augustine, his first missionary to Britain, who asked him how bishops ought to converse with their clerks, among other remarks he replied, ” Because, my brother, having been educated in the monastic rule, you ought not to keep aloof from your clerks: in the English Church, which, thanks be to God, has lately been converted to the faith, you should institute the same system, which has existed from the first beginning of our Church among our ancestors, none of whom said that the things which he possessed were his own, but they had all things common.” When Cuthbert, therefore, came to the church or monastery of Lindisfarne, he taught the brethren monastic rules both by his life and doctrines, and often going round, as was his custom, among the neighbouring people, he kindled them up to seek after and work out a heavenly reward. Moreover, by his miracles he became more and more celebrated, and by the earnestness of his prayers restored to their former health many that were afflicted with various infirmities and sufferings; some that were vexed with unclean spirits, he not only cured whilst present by touching them, praying over them, or even by commanding or exorcising the devils to go out of them; but even when absent he restored them by his prayers, or by foretelling that they should be restored; amongst whom also was the wife of the prefect above mentioned.

There were some brethren in the monastery who preferred their ancient customs to the new regular discipline. But he got the better of these by his patience and modest virtues, and by daily practice at length brought them to the better system which he had in view. Moreover, in his discussions with the brethren, when he was fatigued by the bitter taunts of those who opposed him, he would rise from his seat with a placid look, and dismiss the meeting until the following day, when, as if he had suffered no repulse, he would use the same exhortations as before, until he converted them, as I have said before, to his own views. For his patience was most exemplary, and in enduring the opposition which was heaped equally upon his mind and body he was most resolute, and, amid the asperities which he encountered, he always exhibited such placidity of countenance, as made it evident to all that his outward vexations were compensated for by the internal consolations of the Holy Spirit.

But he was so zealous in watching and praying, that he is believed to have sometimes passed three or four nights together therein, during which time he neither went to his own bed, nor had any accommodation from the brethren for reposing himself. For he either passed the time alone, praying in some retired spot, or singing and making something with his hands, thus beguiling his sleepiness by labour; or, perhaps, he walked round the island, diligently examining every thing therein, and by this exercise relieved the tediousness of psalmody and watching. Lastly, he would reprove the faintheartedness of the brethren, who took it amiss if any one came and unseasonably importuned them to awake at night or during their afternoon naps. “No one,” said he, “can displease me by waking me out of my sleep, but, on the contrary, give me pleasure; for, by rousing me from inactivity, he enables me to do or think of something useful.” So devout and zealous was he in his desire after heavenly things, that, whilst officiating in the solemnity of the mass, he never could come to the conclusion thereof without a plentiful shedding of tears. But whilst he duly discharged the mysteries of our Lord’s passion, he would, in himself, illustrate that in which he was officiating; in contrition of heart he would sacrifice himself to the Lord; and whilst he exhorted the standers-by to lift up their hearts and to give thanks unto the Lord, his own heart was lifted up rather than his voice, and it was the spirit which groaned within him rather than the note of singing. In his zeal for righteousness he was fervid to correct sinners, he was gentle in the spirit of mildness to forgive the penitent, so that he would often shed tears over those who confessed their sins, pitying their weaknesses, and would himself point out by his own righteous example what course the sinner should pursue. He used vestments of the ordinary description, neither noticeable for their too great neatness, nor yet too slovenly. Wherefore, even to this day, it is not customary in that monastery for any one to wear vestments of a rich or valuable colour, but they are content with that appearance which the natural wool of the sheep presents.

By these and such like spiritual exercises, this venerable man both excited the good to follow his example, and recalled the wicked and perverse from their errors to regularity of life.

***********************************************************************************************************

So this story, charming as it is, is about doing ordinary stuff as well as you are able. Whether you are trying to teach and persuade a community of habit-bound monks (I can imagine the supressed sigh when Cuthbert turned up each morning and began again on the same sermon …), or keeping yourself awake at night to make time for prayer, or encouraging the local people in the practice of their faith, or praying the psalmody on their behalf – these are the day to day tasks of the monastery, and as long as Cuthbert was still living with the community, he focussed on doing these things to the best of his ability. There is no record here of him day-dreaming his days away with romantic visions of hermitage.

“Abba Poemen said, ‘Life in the monastery demands three things; the first is humility, the next is obedience, and the third which sets them in motion and is like a goad, is the work of the monastery.'” AC Poemen 103

There is sometimes a requirement “to have some experience of community living before embarking on hermitage. “The experience matured over the course of the history of the vocation suggests that those who feel the inclination, be asked for a time of discernment and formation in a monastery or another community of consecrated life under the guidance of an experienced person …” HLPC 31

This might remind us of that earlier story of St Anthony, who, when he began to question his life in hermitage, and to wander around looking for a different answer, was advised by an angel to go back to his hermitage and get on with his work! Perseverance in the mundane and everyday is a much treasured grace of the hermitage. Complaints about the inevitable days of accidie (frustration, boredom, meaninglessness, doubt) are met with a rather short response:

“An old man had a disciple who for many years had obeyed him in everything. Now one day when he was attacked by the devil, he made a prostration before the old man saying, ‘Let me become a monk on my own.’ The old man replied, ‘Survey the district and we will build a cell for you.’ So they found a place a mile away. They went there and built the cell. The old man said to the brother, ‘What I tell you to do, do it. Each time you are afflicted, eat, drink, sleep, only do not come out of your cell until Saturday; then come to see me.’ The brother spent two days according to these orders, but the third day, a prey to accidie, he said to himself, ‘Why did the old man arrange that for me?’ Standing outside his door he sang many psalms, and after sunset he ate, then went to lie down on his mat to sleep. But he saw an Ethiopian lying there who gnashed his teeth at him. Driven by great fear, he ran to the old man, knocked on his door and said, ‘Abba, have pity on me, open the door.’ The old man, seeing he had not obeyed his instructions did not open it till morning, very early; then he opened it, and found him outside imploring him to help him. Then, full of pity, he made him come inside. The other said, ‘Father, I need you; on my bed I saw a black Ethiopian as I was going to sleep.’ The old man replied, ‘You suffered that because you did not keep to my instructions.’ Then, according to his capacity, he taught him the discipline of the solitary life, and in a short time he became a good monk.” AC Heraclides 1