Cell: Bede’s Life of St Cuthbert: Chapter XVII

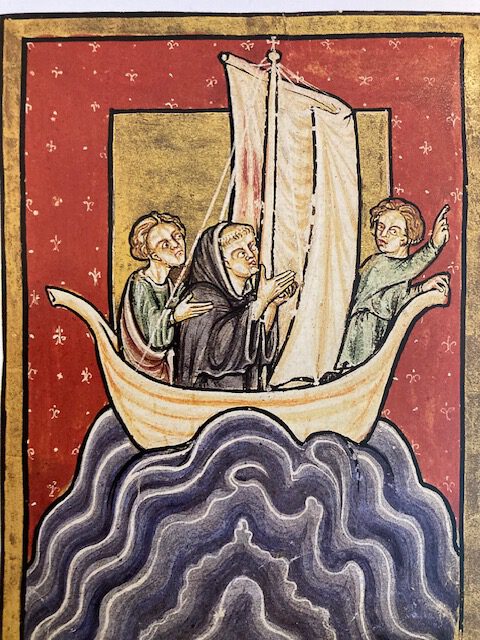

Finally! After much experience of solitude and silence within the community of the monastery, Cuthbert, with the support and authority of all of his brethren, is let go onto the seas to travel to Farne to establish a hermitage there.

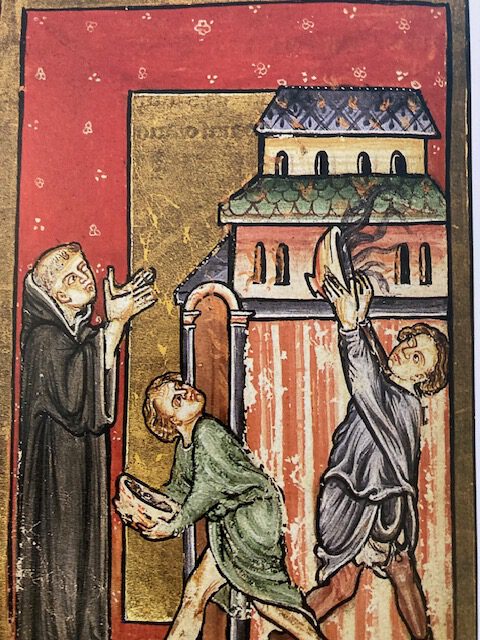

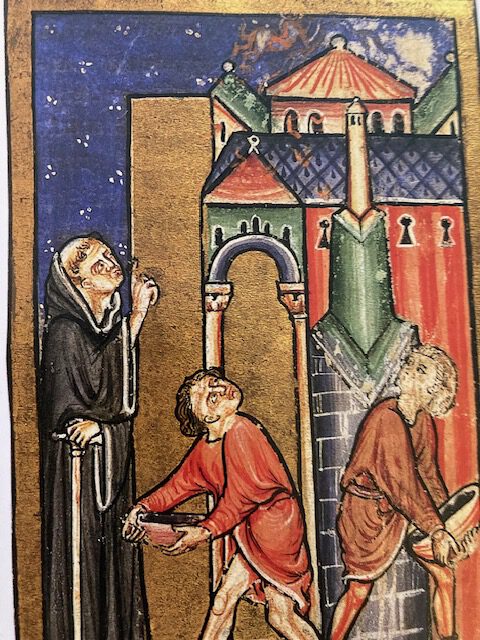

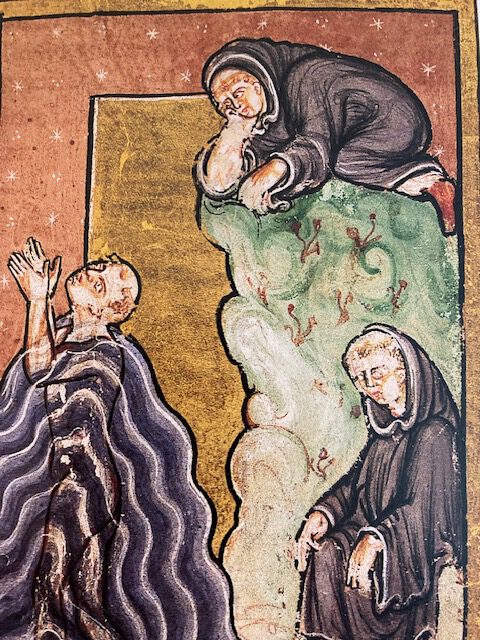

I imagine the relief, and excitement and deep peace which he must have felt. I love that there is a spade-wielding angel waiting there for him, to help him dig the foundations. If you visit Lindesfarne and the Farne Islands in Northumberland you will find the Isle of Hobthrush (St Cuthbert’s Isle – a tidal island near the monastery on Lindesfarne and accessible at low tide), and the Inner Farne. Cuthbert’s cell on the Farne (despite his extensive building works!) is no longer visible, but a short boat ride out there will give you a sense of his isolation when he was living there.

Similarly there is no remains of his cell on Hobthrush, but a Norman tower was built over the spot, and the dip of the foundation for that is still visible, marked by a cross. It gives a sense of how Cuthbert might have spent time there, gazing through the roof to the Northumbrian sky.

OF THE HABITATION WHICH HE MADE FOR HIMSELF IN THE ISLAND OF FARNE, WHEN HE HAD EXPELLED THE DEVILS

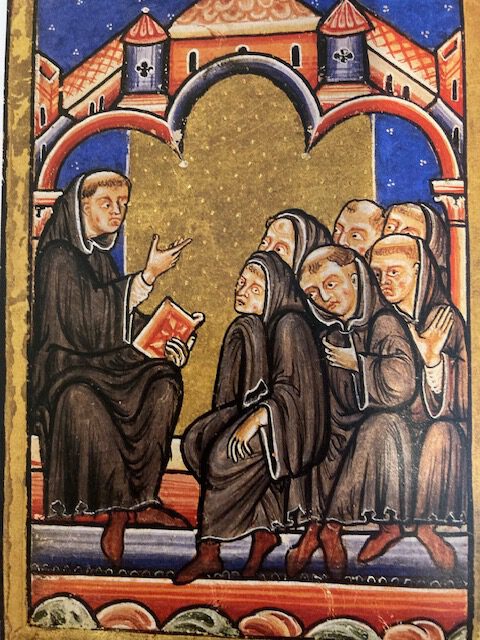

WHEN he had remained some years in the monastery, he was rejoiced to be able at length, with the blessing of the abbot and brethren accompanying him, to retire to the secrecy of solitude which he had so long coveted. He rejoiced that from the long conversation with the world he was now thought worthy to be promoted to retirement and Divine contemplation: he rejoiced that he now could reach to the condition of those of whom it is sung by the Psalmist: ” The holy shall walk from virtue to virtue; the God of Gods shall be seen in Zion. ”

At his first entrance upon the solitary life, he sought out the most retired spot in the outskirts of the monastery. But when he had for some time contended with the invisible adversary with prayer and fasting in this solitude, he then, aiming at higher things, sought out a more distant field for conflict, and more remote from the eyes of men. There is a certain island called Farne, in the middle of the sea, not made an island, like Lindisfarne, by the flow of the tide, which the Greeks call rheuma, and then restored to the mainland at its ebb, but lying off several miles to the East, and, consequently, surrounded on all sides by the deep and boundless ocean. No one, before God’s servant Cuthbert, had ever dared to inhabit this island alone, on account of the evil spirits which reside there: but when this servant of Christ came, armed with the helmet of salvation, the shield of faith, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, all the fiery darts of the wicked were extinguished, and that wicked enemy, with all his followers, were put to flight.

Christ’s soldier, therefore, having thus, by the expulsion of the tyrants, become the lawful monarch of the land, built a city fit for his empire, and houses therein suitable to his city. The building is almost of a round form, from wall to wall about four or five poles in extent: the wall on the outside is higher than a man, but within, by excavating the rock, he made it much deeper, to prevent the eyes and the thoughts from wandering, that the mind might be wholly bent on heavenly things, and the pious inhabitant might behold nothing from his residence but the heavens above him. The wall was constructed, not of hewn stones or of brick and mortar, but of rough stones and turf, which had been taken out from the ground within. Some of them were so large that four men could hardly have lifted them, but Cuthbert himself, with angels helping him, had raised them up and placed them on the wall. There were two chambers in the house, one an oratory, the other for domestic purposes. He finished the walls of them by digging round and cutting away the natural soil within and without, and formed the roof out of rough poles and straw. Moreover, at the landing-place of the island he built a large house, in which the brethren who visited him might be received and rest themselves, and not far from it there was a fountain of water or their use.

***********************************************************************************************************

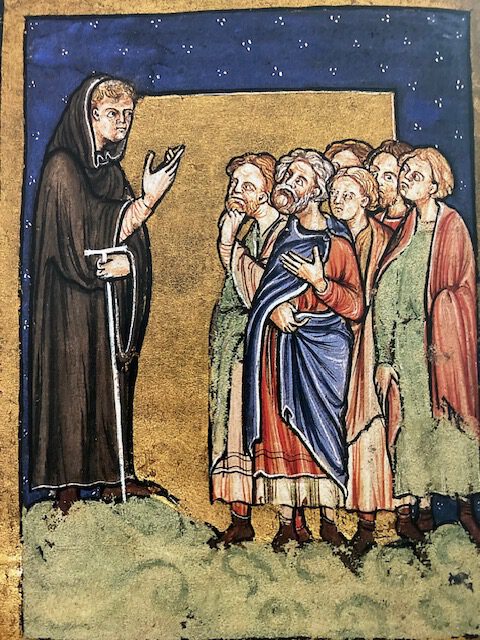

The life of the hermitage is solitary, but it is a solitude which is deeply embedded in the life of Creation – in the heart of Creation. This is true of any hermit (and indeed of any person – the hermit is merely an outward sign of an inward grace which is active in the hearts of all the faithful). The hermit is there in the spaciousness of the Body of Christ – in love for the whole Body, in solidarity, in identity. She inhabits the hermitage as in a tabernacle of the whole of Creation.

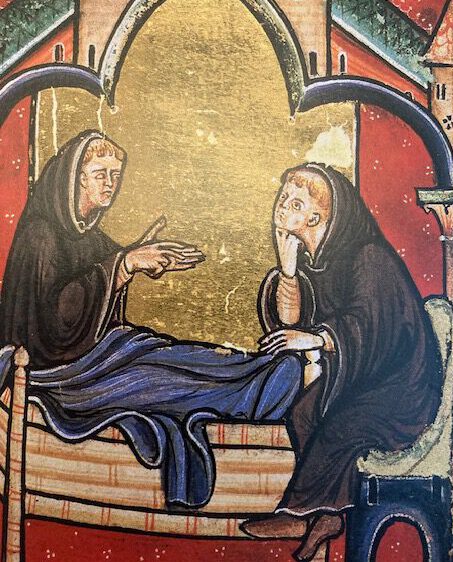

But when a hermit is invited to the profession of Canon 603, and publicly consecrated by the Church in that charism, there is a profound, one might say ontological change. As a liturgical sacrament is “an outward sign of an inner grace” so, by profession and consecration, the hermit enjoins a covenant with the Church, and becomes a sacrament of the Church. An outward sign of an inner grace already received at the heart of the Church. She no longer identifies with the Church, she becomes, “in persona”, the Church, and is recognised by the Church as such.

“She manifests to everyone the interior aspect of the mystery of the Church, that is, personal intimacy with Christ.” cf Catechism 1992 nn 920-921.

In the context of Canon 603, this quotation recognises that the life of hermitage is not a solitary adventure – it is an endeavour of the whole Church. The hermit is hidden – both physically in the figuration of their living arrangements, but spiritually and socially too. They are unlikely to become a public advocate, or a preacher, or given a role in Church leadership. To fully inhabit the charism of c603 that the hermit is called to, they are not seeking personal holiness, nor excellence in study, nor spiritual fame. They are there as the Church themselves.

The desert fathers had a profound – and very practical – understanding of this moment of conversion from God-seeking-individual, to “persona Ecclesia”. As ever the genius of their teaching is to express the spiritual truths they have discovered, in very simple actions. They speak (at some length!) of “dying to your neighbour”

This sounds unnecessarily drastic, and takes a bit of unpicking to retrieve a contemporary meaning.

The monk must die to their neighbour and never judge them at all, in any way whatever. (Abba Moses to Abba Poeman 1)

“To die to one’s neighbour is this: to bear your own faults and not to pay attention to anyone else wondering if they are good or bad. do no harm to anyone, do not think anything bad in your heart towards anyone, do not scorn the man who does evil … this is what dying to one’s neighbour means. do not rail against anyone, but rather say, ‘God knows each one'” (Abba Moses to Abba Poeman 7)

To die to one’s neighbour is to recognise your neighbour in yourself. When you notice a fault in your neighbour, you can recognise the fault in yourself and deal with it there. When your brother is redeemed, then you rejoice to share their redemption.

In his introduction to the Synod on synodality, Pope Francis made an invitation, “Let everyone enter…. Allow yourselves to go out to meet people and to be questioned by people. Let their questions become your questions; allow yourselves to walk together. The Spirit will lead you.”

“Let their questions become your questions”. This is such a rich and poignant and reasonable way of being Church. Pondering the questions and joys and griefs of others, and somehow melding them into the experience of God-with-us in the hermit-tabernacle of our world.

What is redeemed in each, is redeemed in all