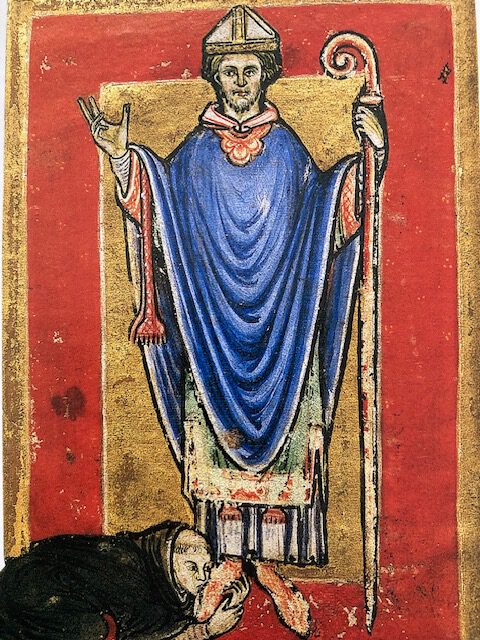

Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: Chapter VII

Cuthbert is in his prime by now. He is a hard worker and taking on responsibilities in the monastery. The community is invited to lay down the foundations for a new Abbey in Ripon, and Cuthbert joins the working party. He was known to be amiable and pleasant with people, and so he was made guest-master at the new monastery.

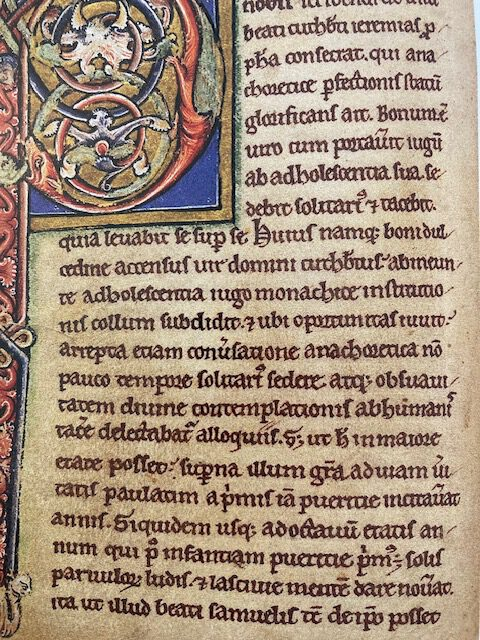

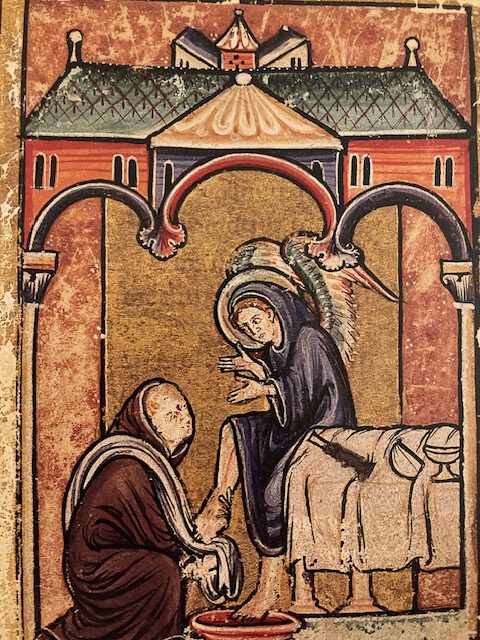

HOW HE ENTERTAINED AN ANGEL, AND WHILST MINISTERING TO HIM EARTHLY BREAD, WAS THOUGHT WORTHY TO BE REWARDED WITH BREAD FROM HEAVEN

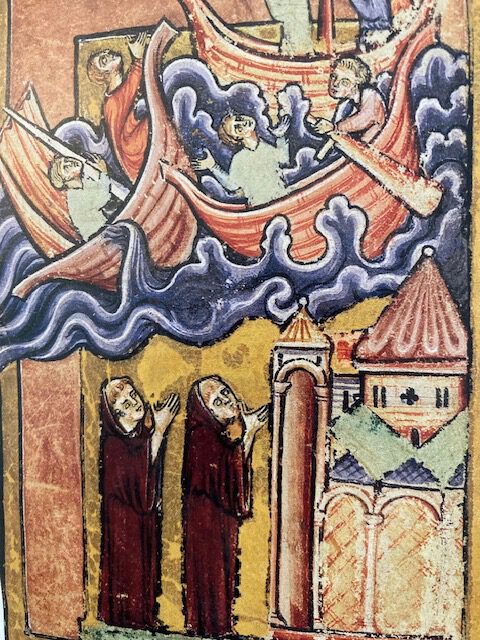

SOME years after, it pleased King Alfred, for the redemption of his soul, to grant to Abbot Eata a certain tract of country called Inrhipum, in which to build a monastery. The abbot, in consequence of this grant, erected the intended building, and placed therein certain of his brother-monks, among whom was Cuthbert, and appointed for them the same rules and discipline which were observed at Melrose. It chanced that Cuthbert was appointed to the office of receiving strangers, and he is said to have entertained an angel of the Lord who came to make trial of his piety. For, as he went very early in the morning, from the interior of the monastery into the strangers’ cell, he found there seated a young person, whom he considered to be a man, and entertained as such. He gave him water to wash his hands; he washed his feet himself, wiped them, and humbly dried them in his bosom; after which he entreated him to remain till the third hour of the day and take some breakfast, lest, if he should go on his journey fasting, he might suffer from hunger and the cold of winter. For he took him to be a man, and thought that a long journey by night and a severe fall of snow had caused him to turn in thither in the morning to rest himself. The other replied, that he could not tarry, for the home to which he was hastening lay at some distance.

Cuthbert washes an angel’s feet.

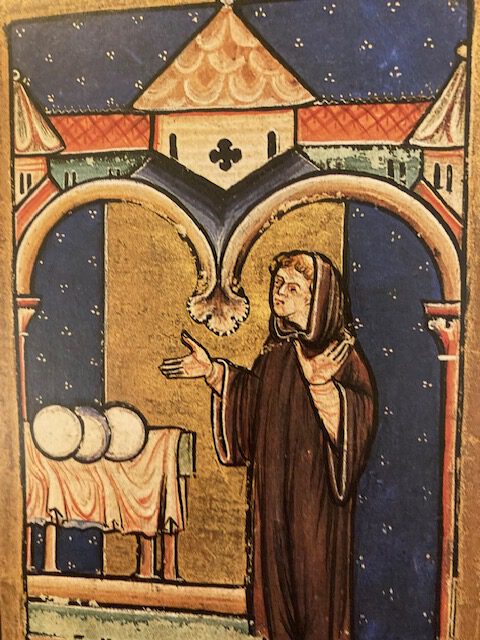

After much entreaty, Cuthbert adjured him in God’s name to stop; and as the third hour was now come, prayer over, and it was time to breakfast, he placed before him a table with some food, and said, ” I beseech thee, brother, eat and refresh thyself, whilst I go and fetch some hot bread, which must now, I think, be just baked. ” When he returned, the young man, whom he had left eating, was gone, and he could see no traces of his footsteps, though there had been a fresh fall of snow, which would have exhibited marks of a person walking upon it, and shown which way he went. The man of God was astonished, and revolving the circumstances in his mind, put back the table in the dining-room. Whilst doing so, he perceived a most surprising odour and sweetness; and looking round to see from what it might proceed, he saw three white loaves placed there, of unusual whiteness and excellence. Trembling at the sight, he said within himself, ” I perceive that it was an angel of the Lord whom I entertained, and that he came to feed us, not to be fed himself. Behold, he hath brought such loaves as this earth never produced; they surpass the lily in whiteness, the rose in odour, and honey in taste. They are, therefore, not produced from this earth, but are sent from paradise. No wonder that he rejected my offer of earthly food, when he enjoys such bread as this in heaven.”

The man of God was stimulated by this powerful miracle to be more zealous still in performing works of piety; and with his deeds did increase upon him also the grace of God. From that time he often saw and conversed with angels, and when hungry was fed with unwonted food furnished direct from God.He was affable and pleasant in his character; and when he was relating to the fathers the acts of their predecessors, as an incentive to piety, he would introduce also, in the meekest way, the spiritual benefits which the love of God had conferred upon himself. And this he took care to do in a covert manner, as if it had happened to another person. His hearers, however, perceived that he was speaking of himself, after the pattern of that master who at one time unfolds his own merits without disguise, and at another time says, under the guise of another, ” I knew a man in Christ fourteen years ago, who was carried up into the third heaven.”

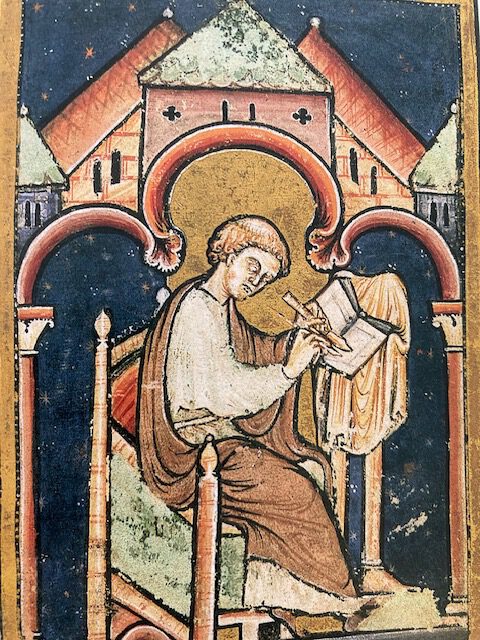

The miraculous loaves from paradise

***************************************************************************************************************

The spirituality of Cuthbert and his brethren was derived from three influences. The Angles and Celts, the Romans, and the Desert Fathers and Mothers. These latter were people who left the comfort and leisure of the cities to go out and meet God in the desert, both pre and post the life of Jesus. With the adoption of Christianity by the Romans in the era of Constantine’s reign (306-337), the persecution of Christians was largely ended. So, somewhat to substitute for the travails of martyrdom, there grew to be a greater desire and excitement for an encounter with God in the desert. As the numbers mounted, small groups of hermitages or Lauras were formed and the hermits began to teach one another. Many of their sayings were written down in various forms, and were eventually pulled together into a collection we now call the Apothegmata (or Sayings). The version I am using is a compilation and translation by Benedicta Ward (BW in the references). It is published by Penguin Classics, and is grouped according to topics, and NOT the alphabetic version with which she is also involved. The page numbers should enable you to follow if you are interested.

For the Desert Fathers and Mothers (and indeed, any desert dwellers) hospitality was an unwritten law of the desert. With the arid desert and the life/death balance of desert-living often on the edge, a request for life-saving water or shelter was never to be refused.

“A brother came to a hermit and as he was taking his leave he said, ‘Forgive me Abba for preventing you from keeping your rule@. The hermit answered, ‘My rule is to welcome you with hospitality, and to send you on your way in peace’. TDF 136

The situation for Cuthbert was not much different. It is clear from the stories of his travels that he often stopped off and relied on strangers’ hospitality for food and a bed. And when travellers arrived at the monastery, in his role as guest-master, he was expecting to invite them in and see to their wellbeing before sending them on their way again.

It is worth noting that both of these forms of hospitality were directed towards meeting the needs of the travellers, and not necessarily their desires. “Guests” were seldom invited to linger for long, neither in the desert, nor in the monastery. Indeed there are many examples in the Apothegmata of the Desert dwellers avoiding or even turning away visitors who have arrived out of curiosity or a sort of fandom.

Once a provincial judge heard of Moses and went to Scetis to see him. They told Moses that he was on his way, and he got up and fled towards a marsh. The judge and his entourage met him, and asked him, ‘Tell me, old man, where is the cell of Moses?’ He said, ‘What do you want to see him for? He’s a fool and a heretic.’ The judge came to the church, and said to the clergy, ‘I have heard about Moses and I came to see him. But I met an old man on the way to Egypt, and I asked him where the cell of Moses was and he said, ‘Why are you looking for him? He is a fool and a heretic.”’ The clergy were distressed and said, ‘What sort of person was your old man who told you this about the holy man?’ He said, ‘He was an old man, tall and black, wearing the oldest possible clothes.’ The clergy said, ‘That was Moses. He said that about himself because he didn’t want you to see him.’ The judge went away very impressed. AC Moses 8

The contemporary hermit faces the same conundrum: how to offer a (life-supporting?) hand to those who need it, without compromising the solitude and silence of the hermitage. Perhaps the hunger and thirst which todays’ travellers arrive with are as much for rest, peace, a meaningful sense of God, as for the physical need for food, water and shelter.

Evenso, this ancient and longstanding principle of a hospitality of necessity rather than desire seems a good guideline. As part of my C603 Rule of Life, I promise that I will “live simply, in solitude and silence, staying and returning there insofar as duties permit”. So duties such as caring for elderly parents, celebrating a family wedding, earning a suitable living, Sunday Mass – and returning with haste to my “cell” (as the Apothegmata would name it) seems to give a good balance.

And what of the strangers who ask for prayers, or counsel, or “a Word” (ref also Apothegmata). I often fall back on the words of Raphael Vernay – a Benedictine Hermit ”The hermit is simply a pioneer in the way of the desert which the whole of humanity must follow of necessity one day, each one according to their own measure and desire. This eremitical vocation, at least embryonically, is to be found in every Christian vocation. It is necessary that the Church and society do something so that this may be realizable, so that each may at least touch it, be it only with the tip of their little finger”. Benedictine Raphael Vernay: On the Desert Place of the Inner Sanctuary. 1974

Opening the window of the hermitage through blogs like this, or the work other hermits eg. Sr Laurel O’Neil on C603, or Sr Wendy Becket on Art appreciation (RIP 2018), or Sr Catherine Wybourne on using technology as an evangelical tool (RIP 2022), or any other hermit on their particular speciality, seems a good and appropriate and measured way of enabling each person to touch hermitage, “be it only with the tip of their little finger”. We hope and pray for you that these glimpses through a barely open window might offer succour and support in times of need. God is with you.