Mutuality: Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: Chapter XII

The capacity to commune and cooperate with the animals – eagles, otters, horses, ravens (soon!) is a common trope amongst the hagiographies of the Celtic saints. It reflects a sense of mutuality between ourselves and the rest of creation. Perhaps an ecological mutuality which needs to be nurtured in these days of growing concern for the wellbeing of our planet.

I love the final image of this story – Cuthbert and his companion, with the householders of the village, frying fish around an open fire, and the eagle still with her own portion of fish to feed her young. All contributing, all partaking. Is that not the essence of mutuality?

HOW HE FORETOLD THAT, ON A JOURNEY, AN EAGLE WOULD BRING HIM FOOD, AND HOW THIS TOOK PLACE ACCORDINGLY

IT happened, also, that on a certain day he was going forth from the monastery to preach, with one attendant only, and when they became tired with walking, though a great part of their journey still lay before them ere they could reach the village to which they were going, Cuthbert said to his follower, “Where shall we stop to take refreshment? or do you know any one on the road to whom we may turn in ? “-” I was myself thinking on the same subject,” said the boy; “for we have brought no provisions with us. and I know no one on the road who will entertain us, and we have a long journey still before us, which we cannot well accomplish without eating. ” The man of God replied, ” My son, learn to have faith, and trust in God, who will never suffer to perish with hunger those who trust in Him.” Then looking up, and seeing an eagle flying in the air, he said, ” Do you perceive that eagle yonder? It is possible for God to feed us even by means of that eagle.” As they were thus discoursing, they came near a river, and behold the eagle was standing on its bank. “Look,” said the man of God, “there is our handmaid, the eagle, that I spoke to you about. Run, and see what provision God hath sent us, and come again and tell me.”

The boy ran, and found a good-sized fish, which the eagle had just caught. But the man of God reproved him, ” What have you done, my son? Why have you not given part to God’s handmaid? Cut the fish in two pieces, and give her one, as her service well deserves.” He did as he was bidden, and carried the other part with him on his journey. When the time for eating was come, they turned aside to a certain village, and having given the fish to be cooked, made an excellent repast, and gave also to their entertainers, whilst Cuthbert preached to them the word of God, and blessed Him for his mercies; for happy is the man whose hope is in the name of the Lord, and who has not looked upon vanity and foolish deceit. After this, they resumed their journey, to preach to those among whom they were going.

***********************************************************************************************************

Canon 603 makes this rather cryptic statement about the purpose of the hermit’s separation from the world being the salvation of the world. “The Church recognises the life of hermits or anchorites, in which Christ’s faithful withdraw further from the world and devote their lives to … the salvation of the world.” This takes a little unpacking. and is perhaps best explained by the principle of mutuality.

“The hermit who distances themselves from the world does not flee out of fear or contempt. They lived in the world, and were called, Christianly, to seek to love it and to look at it with the eyes and the love that God revealed to us in Jesus, who loved the world until the end. Without the world, one cannot conceive of an exit from the world: one separates oneself from the world to save it, one moves away to integrate it, The exterior thus become interior, the distant becomes near, the excluded is desired included. This is why separating does not mean fleeing. HLPC 24

Mutuality is a bit like solidarity – but more so! Solidarity generally involves standing alongside others; mutuality goes one step further to identify with the other. We will discuss in a later post how this is formalised in the covenant of solemn profession and consecration. At this point though we are considering something less formal, but just as intimate and world-changing. I have mentioned before the words of Pope Francis with respect to the Synodal processes of the Church. They are very useful words “No one is to be left out; let them all in; let them ask questions. Let their questions become your questions”

How is this translated specifically into the language and spirituality of the hermitage?

I am going to go off-piste a little here by considering, the “ecclesiological model” of hermitage, using the teachings of St Peter Damien.

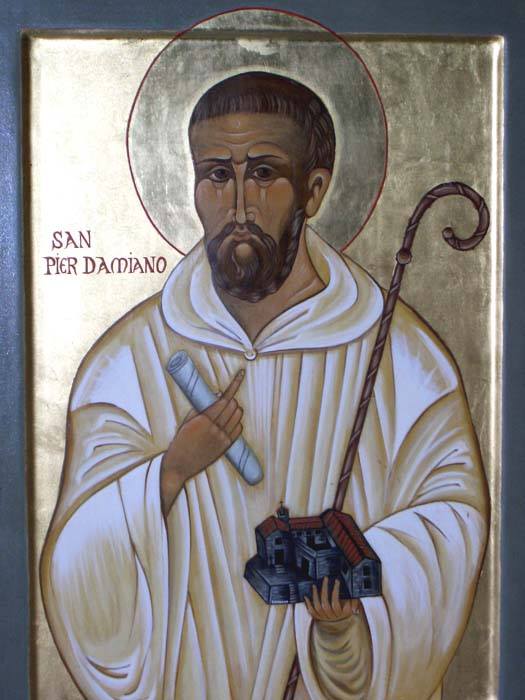

Peter was an 11th century Benedictine hermit/bishop. (ref image attached). One of the great debates occupying the minds of the hermits of the day, was the question of praying on your own. When a hermit was praying in solitude, could they legitimately pray the call/response “The Lord be with you” “And also with you”? Peter wrote a whole book about it, and his answer was a resounding “YES!”.

“Indeed the Church of Christ is united in all her parts by such a bond of love that her several members form a single body and in each one the whole Church is mystically present, so that the whole Church Universal may rightly be called the one Bride of Christ, and on the other hand every single soul can, because of the mystical effect of the Sacrament, be regarded as the whole Church”.

from The Book of “The Lord be with you” (Dominus Vobiscum) a treatise by St Peter Damien, Bishop and Doctor of the Church. (1007-1072).

His teaching was that as each hermit is created in the image of Christ – confirmed by baptism – so each hold within them the fullness of Christ – the fullness of Church. Peter went so far as to say that each hermit is Church unto themself.

It took me a long while to get a sense of what hermitage was for. I knew it was “home”, the place I was meant to be, but what was I supposed to be doing here? The answer perhaps lies in this theology of ecclesiology. If the hermit is the fullness of Church in themself, then whatever is redeemed in the solitary hermit, is also redeemed in the whole of the Church. And, (ref multiple posts) whatever is true of a hermit is also true of everyone else – so, whatever is redeemed in each and every member of Christ, is redeemed in the whole Church too. This is surely the ultimate in mutuality?