Penance: Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: Chapter VIII

I wrote this piece on penance for the Redemptorist Sunday publications a few years ago. I don’t think I could write anything better today. I particularly like the phrase “turning to face the headwind of truth with courage” in my Redemptorist piece, and the phrase “fruits worthy of repentance” in the Life of St Cuthbert. (I have highlighted them in the text). Both encourage the commitment to reformation, to change, within the context of the reality of our particular circumstance.

HOW CUTHBERT WAS ZEALOUS IN THE MINISTRY OF THE WORD

AFTER the death of Boisil, the priest beloved of God, Cuthbert took upon himself the duties of the office of prior before mentioned; and for many years he was busy with spiritual works, as befitted a holy man; for he not only furnished both precept and example to his brethren of the monastery, but sought to lead the minds of the neighbouring people to the love of heavenly things. Many of them, indeed, profaned the faith which they professed, by unholy deeds; and some of them, in the time of plague, forgetting the sacred mystery of the faith into which they had been initiated, had recourse to idolatrous remedies, as if by charms or amulets, or any other mysteries of the magical art, they were able to avert a stroke inflicted upon them by the Lord. To correct these errors, he often went out from the monastery, sometimes on horseback, but more often on foot, and preached the way of truth to the neighbouring villages, as Boisil, his predecessor, had done before him.

It was at this time customary for the English people to flock together when a clerk or priest entered a village, gladly listening to what was said, and still more gladly following up by their deeds what they could hear and understand. So great was Cuthbert’s skill in teaching, so great his love of driving home what he had begun to teach, so bright the light of his angelic countenance, that none of those present would presume to hide from him the secrets of their heart, but they all made open confession of what they had done, because they thought that these things could certainly never be hidden from him; and they cleansed themselves from the sins they had confessed by “fruits worthy of repentance” as he commanded. He was mostly accustomed to travel to those villages which lay in out of the way places among the mountains, which by their poverty and natural horrors deterred other visitors. Yet even here did his devoted mind find exercise for his powers of teaching, insomuch that he often remained a week, sometimes two or three, nay, even a whole month, without returning home; but dwelling among the mountains, taught the poor people, both by the words of his preaching, and also by his own holy conduct.

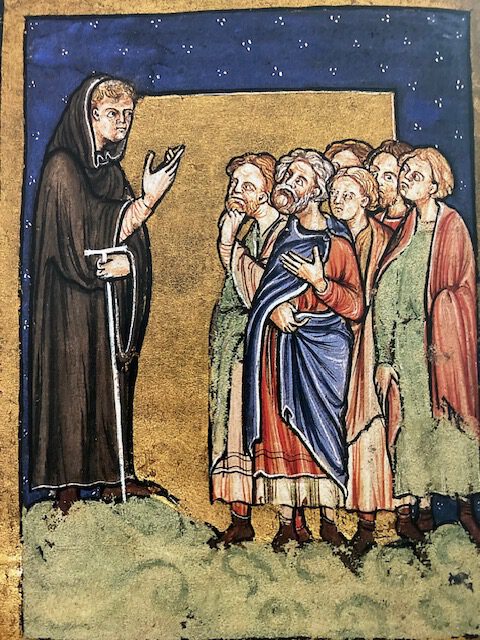

Cuthbert preaching

**********************************************************************************************************

Canon 603 states, amongst other things, that life in the hermitage is to be a life of “assiduous prayer and penance”. Assiduous prayer is probably a familiar, if challenging concept for most people, but assiduous penance? The dictionary definition of penance is self-inflicted punishment. Assiduous self-punishment sounds frankly terrifying! And neither healthy nor sensible in the context of a lifelong commitment.

So how to live out “assiduous penance” safely and with integrity? The life of the hermitage is a simple life – much of the flummery and dissemblance of social living is withdrawn, so that what is most fundamental and foundational to our being human can emerge. When we shed some of those artifices, it can be a very joyful and freeing experience, but it can also be challenging and uncomfortable. The willingness to engage with that experience of reality, is penance lived assiduously.

The original Greek for the Latin “repentance” (from which penance is derived) is metanoia, which means turning around. Penance is the intentional act of turning around – not glancing back fearfully over the shoulder, but turning to face the headwind of truth with courage. Penance is to try to live without a barrier between ourselves and the truth.

I think the natural world sets an excellent example of this sort of penance. The penance in nature is necessarily constant and assiduous – a tree has no contrived defence against the elements, but must bend as the wind blows, flourish with the sun and strain its roots deep for the source of water, responding to drought, sunlight, coldness and heat as they present themselves. A tree grows in its place, in the conditions in which it finds itself. It abides in the stark reality of its circumstance.

So how might this penance, this “engaging with reality” manifest itself in practice? How might it change our behaviour towards our world and each other? Perhaps the growing awareness of those issues which degrade the balance of the ecosystems of our planet might make a good and simple example to begin with.

There is an increasing awareness that some of the perks of modern living are delusional: the excessive fuel we burn, the unnecessary food we waste, the undegradable plastics we pollute with; all of these are distortions of the ecological balance which underpins our world. The truth is that living in this way is not sustainable. There is “fruit worthy of repentance” to be found here. Our penance – our “turning, to face the headwinds of truth” – is to live within the bounds of what is sustainable. What is a practicable, fruitful, assiduous change that could repent us? What could align us closer to the reality of our created humanity?